What does quality education mean to you? Would it mean the same thing to the person next to you? If the goal posts of quality are understood differently at various levels of the system, can quality really be achieved?

The idea of quality education in countries like Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan has been thought of as a blend of academic learning (ilm/ta’lim/obuchenie which translates as knowledge and academic/subject matter learning) and social upbringing (akhloq/tarbiya/vospitanie which translates as ethics, ethical/social upbringing) since the pre-Soviet era. How do the post-Soviet opportunities and challenges of globalisation, plurality, and uncertainty affect these understandings, especially at the school and community levels?

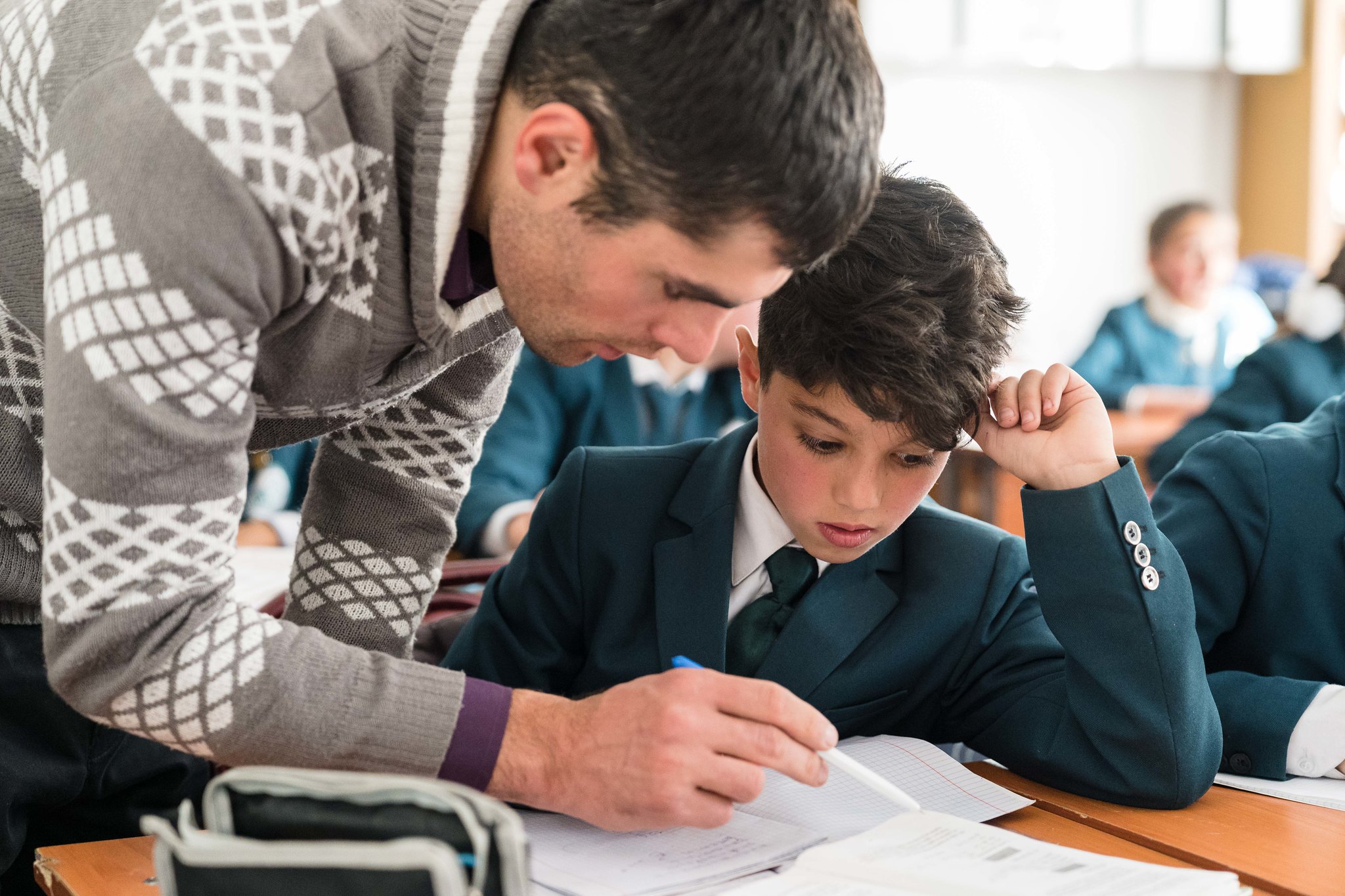

If school leaders are responsible for shaping schooling, teachers for delivering quality instruction, and parents and students engaging and participating in these processes, we see that quality from the system-level down to the ground depends on a whole ecosystem of interpretations and practices of all these actors. Education policies may be well-intentioned, but without understanding and building upon views from classrooms and communities, how can we be sure they fit the knowledge, needs and aspirations of those the education system seeks to serve? Furthermore, we need to ask what quality implies for systems that are under-resourced and for teachers that are underprepared, who, nevertheless, are expected to prepare their Central Asian students, communities, and nations to address the enormous challenges at local, national, regional, and global scales.

Against this background, our particular research project, by consulting teachers, students, school leaders and parents, seeks evidence-based, actionable, and contextually relevant insights and strategies to improve holistic learning outcomes for children and young people within their classroom and school. The study aims to produce data and analyses that are relevant to the first of five themes laid out in the Schools2030 Call for Proposals, Effective teaching strategies to raise holistic learning outcomes. Our theme centring on quality in education is not only of great significance in itself, but also because it extends to other important themes, especially stakeholders’ perspectives on equity and inclusion in quality education, their ideas about how to ensure equitable, inclusive education, and how to address structural barriers to quality education.

Our research focuses on identifying local stakeholders’ (teachers, students, school leaders, and parents) perspectives towards quality education, the challenges to quality and possible responses to these challenges. We will look to understand what meaning and values the local stakeholders attach to the concept of quality, as well as identify effective, sustainable, culturally relevant, and contextually workable solutions that are taking place in the classroom, that may be replicable in countries like Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. Beyond this, the rich and grounded accounts of the local stakeholders’ perspectives will enable us to compare local stakeholders’ concepts of quality with those that exist in the region and globally and provide insights and implications for policy, programmes, and pedagogical practices on improving quality education in the schools and systems in Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan.

Our research asks: What classroom and school-based practices and ideas are effective, sustainable, culturally relevant, and contextually workable? How can such solutions be developed in countries like Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan? We will gather data through focus groups and interviews, observations, survey questionnaires, and local education-related documents. Our method is itself equitable and inclusive, as it treats the local stakeholders as significant partners in the education process and engages them in articulating and reflecting on their experiences, attitudes, and aspirations.

The research takes place amid the frequently reported increasing gaps in learning outcomes between the Global South and North, Central Asia and OECD countries. Within Central Asia, gaps in quality learning are increasing between regions and across gender, urban and rural localities, languages, school types and other dimensions and differences. The implications of these inequalities are alarming in terms of individual and family aspirations for a better quality of life, social and intercultural/interethnic cohesion, and peaceful national and regional development and prosperity. Our overarching theme of stakeholder perspectives on quality education, therefore, intends to inform the entire educational process and the ability of schools and communities to develop school-based initiatives that both support learners’ growth and are satisfactory to the needs and aspirations of students, their parents and communities, school leaders and teachers, education administrators and policymakers.

Such multi-stakeholder dialogue on policy and planning is expected to have a transformative impact through its contribution to collaborative deliberation within and across stakeholder groups leading to local empowerment and capacity development at the individual, school, and community levels.

*ideas expressed are the authors’ and not necessarily reflective of those of CIDEC.